Exhibition

32,000 Beaches

Australian Exhibition

The Flood: 2nd International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam IABR05

Exhibitors: Richard Black, RMIT Architecture Senior Lecturer, Martyn Hook, RMIT Architecture Senior Lecturer, RMIT Architecture Upperpool Design Studio Students; Adrian Iredale, Master of Architecture (by research project), Finn Pederson, Master of Architecture (by research project), Brian Donovan, Master of Architecture (by research project), Timothy Hill, Master of Architecture (by research project), Stephen Neille, Master of Architecture (by research project), Scott Balmforth, Master of Architecture (by research project), Richard Blyth, PhD in Architecture (by research project), Gerard Reinmuth, Master of Architecture (by research project)

Biennale Exhibition Review:

The Flood: The 2nd International Architecture Biennale, Rotterdam and the Australian Exhibition “32,000 Beaches”, curated by Leon van Schaik

Reviewer: Sarah Quigley

Architecture Australia, Sept/Oct 2005

LAS PALMAS IS the main venue for Rotterdam’s 2nd International Architecture Biennale, and seen from across the Maas River it looks imposing. It’s only when you get close that its shabbiness becomes apparent: peeling facades, cracked windows, and stairs made from blue scaffolding. Once a warehouse for the Dutch East India shipping line, it’s like an icon for the port city – functionality over aesthetics, commerce at all costs. Flanked on both sides by choppy grey water, the site seems appropriate for a biennale whose central theme is “The Flood”. The overall metaphor covers five exhibitions: The Water City and Mare Nostrum (both in Las Palmas) and three smaller shows at the Netherlands Architectural Institute, Polders, Three Bays and Flow.

The principal curator is Adriaan Geuze, director of the landscape architecture and urban design practice West 8 (itself recently relocated to Las Palmas). His choice of topic is certainly relevant to the Netherlands, whose past, for centuries, has been significantly shaped by water, and whose future depends on taming it. But Geuze stresses the biennale’s international aspect: the complex relationship between architecture and water, and the challenges posed by a changing climate, are global issues. Only by a sharing of inventive techniques can the “mastery and manipulation” of water be achieved.

And so The Water City includes not only models of Dutch cities, but many others: Venice, Brighton, Saint Petersburg, Dubai. In the centre of the dimly lit warehouse, Mare Nostrum offers a similarly international cast. Focused on mass tourism, it brings together seventeen guest curators from seventeen countries, including Brazil, Turkey, Russia, Israel, Scotland, Spain and Australia.

At first the inclusion of Australia in an exhibition entitled “The Flood” seems a paradox. Australia has almost polar-opposite problems from the Netherlands, the latter being concerned with rising water levels, high-density populations and a drastic shortage of land. But Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”) refers to the Roman appropriation of the Mediterranean, and leads naturally to a debate on modern tourists and their invasion of coastlines worldwide, including Australia’s.

Most curators here have analysed waterfront development in their countries, and discussed the problems raised by a world where tourism has become ultra-cheap and readily available. The seventeen national displays arrow out from a huge central lightbox, emblazoned like a tourist brochure (Ipanema is touted as “Best Beautiful People Beach!”, Mexico’s Maroma Beach “Best Romantic Beach!” and so on). Dismaying statistics reveal the rise of mass tourism over past decades, and the growing penchant for waterfront attractions. Asia and the Pacific are, it appears, in big trouble. Once remote enough to remain pristine, these destinations are now the newly popular kids on the world block. In 1951 tourist rates stood at 1 per cent; by 2003, they had grown to 17.2 per cent, with numbers still climbing.

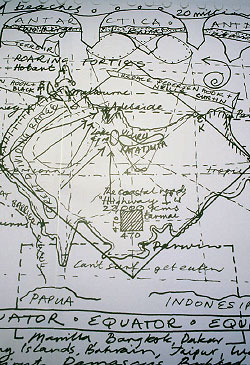

Leon van Schaik, curator of the Australian “32,000 Beaches”, takes a combative approach to this central pillar of doom. His bold hand-drawn map of Australia hangs right beside the main entrance to the room, demanding a viewer’s attention. Its chaotic and supposedly random jottings bring to mind the recent exhibition Content created by Rem Koolhaas, Rotterdam’s most famous and brashest architectural resident.

In style and attitude, van Schaik follows Koolhaas’s lead, paying little homage to visual niceties but using content to great effect. His mind-map appears chaotic, but on closer inspection proves to be the inventive, informed flow of someone who knows his country inside out, and is confident of placing its specific problems (geographical, climatic, topographical) in a world context. By inverting his map, van Schaik locates Australia at the top of the world – and also, in a way, isolates it. His stated aim is to show that Sydney, Adelaide, Perth and Melbourne are not southern versions of European cities, and that Australia, the “driest, oldest and flattest” continent, has a very different set of preoccupations from other water-oriented countries.

The problems highlighted in “32,000 Beaches” are often paradoxical. Not enough water, too much coastline. A tourist industry attracted by the natural environment, which is fast losing its attractiveness due to tourists. Add to this a harsh climate, industrial pollution and the fact that 80 per cent of Australians live near the coast, in several major cities that severely deplete water resources, and you have just some of the problems facing Australian architects and urban planners today.

Below van Schaik’s map stretches a long table covered in maps, surveys and texts. These represent the work of five commissioned architects or architectural teams, including Iredale Pedersen Hook and Stephen Neille, Richard Black and RMIT students. They both identify and offer solutions to five problem areas: the strip-densification of the east coast from Sydney to Brisbane, holiday developments south of Sydney, the linear city of west-coast Perth, the invasion of Tasmania by seekers of solitude, and the mouth of the Murray Darling Basin, in grave danger from increasing salinity.

Proposals range from the practical to the imaginative: aquaculture parks and marinas, extended piers, floating accommodation and regenerated coastal habitats. Often, as with Martyn Hook’s analysis of Port Phillip Bay, the approach is to look back to the first European settlers, identify where problems arose, and offer new solutions for occupying the water’s edge in an environmentally sensitive way. Solutions are neither nostalgic nor naive; tourist development must be allowed to continue, but must follow intelligent routes.

A summary of this half-restorative, half-innovative approach is provided by van Schaik. “Since 1812 Aussies have been dreaming about an Inland Sea,” he writes. “Let’s finally build the bitch! We’ll soak up the increased oceanic volume AND make more shoreline. Why not make a few bucks for more waterside development while saving the world?” He’s speaking tongue-in-cheek, of course, but his quip points the way to where architectural planning could go, if managed properly. A more complex interweaving of urban building and natural environment could save Australia from becoming another Mexico or Spain, groaning under the weight of mass tourism, propped up temporarily by hasty coastal developments, infrastructures and environments close to collapse.

Seen in the wider context of the biennale, Australia emerges in a positive position: a country with a healthy economy, a history of design experience and architectural ingenuity. It’s unburdened, moreover, by the problems of countries such as Russia or Cuba, struggling with complicated political pasts, needing to Westernize their social structures while simultaneously marketing themselves as tourist destinations.

Oddly enough, the closest parallel to Australia is the Croatian exhibition. Its seven models, beautiful in their white simplicity, appear a little like the child Australian architecture once was. Land previously locked up – a prison island, an old quarry – has now become free for different usage. The Croatians’ approach of both protecting the environment and opening it up for tourism is similar to that of (the albeit more advanced) Australia.

On his map van Schaik has drawn a plane, arrowing straight from Melbourne to Rotterdam. “32,000 Beaches” in the canal-riddled Netherlands – an odd fusion, but it works. In spite of obvious differences, there’s a sense of symbiosis: shared optimism, shared realism and a shared belief in the future of intelligent architecture.

Design Studio

Flood, RMIT Architecture Upperpool Design Studio, Semester 2, 2005

Studio Leaders:

Richard Black, RMIT Architecture Senior Lecturer

Martyn Hook, RMIT Architecture Senior Lecturer

An RMIT Architecture Studio was commissioned addressing the brief for the Biennale, with resulting student work being exhibited along with practice work from across Australia.

Workshop

Flood Resistant Housing Workshop

International Design Masterclass Workshop

2nd International Architecture Biennale, Rotterdam 2005

Workshop leader:

Greg Lynn, Practice Director: form

Student Award

RMIT Student wins Biennale student award. RMIT Architecture student John Doyle led the international collaborative student workshop group ‘Oyster’ that won the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam IABR05 Student Award

Oyster Group:

John Doyle, RMIT Architecture, Melbourne (Group Leader)

Karola Dierichs, Architectural Association, London

Teresa Nai-Tsuei Yeh and Naiwen Cheng, Berlage Institute, Rotterdam

JURY:

Hans Beunderman (Chairman)

Kurt Forster

Adriaan Geuze

Greg Lynn

Lucas Verweij

Jury Comments:

“The group ‘Oyster’ has integrated not only landscape and architecture, but also made infrastructure an integral part of the project. They innovated building forms and created an alternative lifestyle… The winning project of the IABR student award, the Oyster composed of a molded landscape of a-centric rings, which mimic flood lakes. The home acts much like an oyster allowing water to penetrate its fortress for survival and nutrition, while protecting its precious center.”

IABR05 PRESS RELEASE

“Architecture Biennale Student Award presented”

International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam

Rotterdam June 2, 2005

Wednesday evening June 1, the Architecture Biennale Student Award was presented during the final presentation of the Masterclass ‘Flood Resistant Housing’. Hans Beunderman, Dean of the Delft University of Technology, presented the award to students of the group ‘Oyster’.

The jury, chairman Hans Beunderman, Kurt Forster, Adriaan Geuze, Greg Lynn and LucasVerweij, stated that the group ‘Oyster’: “ has integrated not only landscape and architecture, but also made infrastructure an integral part of the project. They innovated building forms and created an alternative lifestyle.”

The students of the group ‘Oyster’ are: Karola Dierichs (Architectural Association, London), John Doyle (RMIT, Australia), Teresa Nai-Tsuei Yeh and Naiwen Cheng (both from the Berlage Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands)

During the 2nd International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam, American Architect Greg Lynn guided the masterclass ‘Flood Resistant Housing’. Over sixty architecture students and young architects from all over the world focused on finding new ways for building houses in the flood risk areas of the city of Deventer, the Netherlands. Their wide variety of projects will be on display at the exposition Flow in the Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAI) till 21 August 2005. This exhibition will be complemented with a video registration of the work in progress during the masterclass and the final results.

The participants of the masterclass are delegated from: the University of Cape Town, RMIT University in Melbourne, Columbia University, Universidad Diego Portales in Santiago de Chile, SCI-Arc in Los Angeles, Architectural Association London, ETH Zürich, University of Zagreb, CEPT School of Architecture in Ahmedabad, the Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana in Yogyakarta, Rotterdam Academy of Architecture and Urban Design, Technical University Delft and Berlage Institute.

The masterclass is organized in collaboration between the Rotterdam Academy of Architecture and Urban Design, the Technical University Delft, the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam, the Netherlands Architecture Institute and the Berlage Institute.

The theme of the second International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam is ‘The Flood’. For one month, from 26 May to 26 June 2005, the exhibitions will be on show at Las Palmas and the Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAI) in Rotterdam. In addition, the Biennale will feature numerous conferences, lectures, excursions, an Open Day and a City Program. The event is intended to become a venue for an international exchange of expertise, historical knowledge and future visions that explore the advantages and disadvantages of living and working with water.”