Consultant: Ian Watts, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)

Design Team: RMIT Architecture Upperpool Design Students:

Amy Melrose, Emily Wallace, Gaudi Olaga, Trecia Lim, Girish Sagram, Lisa Seibert, Matt Dravich, Raphael Fantl, Will Loft and Chung Ho.

Client: Ampilatwatja Community, Alice Springs, Northern Territory

Partners: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)

Ampilatwatja Community, Alice Springs, Northern Territory

National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO)

Project Background:

The average life expectancy for the Aboriginal male is 59 years compared to 77 for a white Australian male. The work presented here is a tiny yet important piece of work that may help ‘close the gap’ in the health status of Aboriginal people. The studio is a live project that remains alive. The studio required 10 students to work collaboratively, well beyond the standard academic requirements, and produce a design for the Ampilatwatja Medical Centre in the Northern Territory.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) helped develop and run the studio, in particular Ian Watts whose tireless work and generosity made the studio possible. We are also very grateful to the community members of Ampilatwatja, who welcomed us and also to the health services staff for their generosity with their time and ideas.

Student Statement:

The studio Home Away From Home was a type of studio that is rare at RMIT. The obvious reasons being for its attempt at tackling the issue of Aboriginality in any form, taking students out of their comfort zone, bringing them to a very small community of 400 Aboriginals 400 kms from the nearest thing called a town. Rarer still was the idea of having ten students design and develop a single project together. Any one of these elements would set Home Away From Home apart, but what can’t be as easily shown on a plan, in a diagram, or through a render was that the members of the studio really cared about what they designed. In short; what was so rare about this studio was the sense of responsibility the students manifested, responsibility to the work, to the users, and to themselves.

Design Studio: Home away from Home:

The design studio group travelled through a seemingly infinite landscape and was then placed within an intense and fragile remote Aboriginal community. They were asked to learn and respect unfamiliar and unique cultural practices and ideas. Big issues such as avoidance, security, privacy, sustainability, responsibility and negotiation became paramount. The group was charged with a sense of the real – the challenge of having to balance between the needs of the community, the medical staff and their tutors. The students responded with a respectful, believable, working piece of architecture.

It is clear that there is a general need for the refurbishment of Aboriginal health service premises, ranging from minor to major repairs. The work at Ampilatwatja, supports this view. The architectural design of the services is of vital interest in the strategy to achieve health equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

About the Ampilatwatja Community:

Ampilatwatja is a progressive Aboriginal community around 320 km and 4 hours drive north-east of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. It includes 3 outstations up to 50 km away. The people of Ampilatwatja form part of the Alywarr tribe who own the land that was given back to them in the 1970’s.

Ampilatwatja is a dry community with a community store, civic office, school, and a medical centre. The medical centre forms an important part of the community and is visited on a regular basis by visiting nutritional and paediatric specialists.

The community is very well known for the art produced by women of the community. The medical centre owns 40 of these paintings and intends to incorporate them within the new building.

Aboriginal Art Directory webpage: Artists of Ampilatwatja

Total Travel webpage: Artists of Ampilatwatja

Public Lecture:

“Learning from Ampilatwatja”

Brendan Jones RMIT Architecture Design Studio Leader, Practice: Antarctica

Ian Watts, Practice: Antarctica. Formerly of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)

and students in the “Home away from Home” RMIT Architecture Upperpool Design Studio, 2008

Thursday 4 June 2009 – 7.00pm

RMIT Building 50, Orr St, Carlton (perpendicular to Victoria St. between Cardigan and Lygon Sts)

Entry by gold coin donation, refreshments provided.

Brendan Jones and Ian Watts will present three challenging design studios run at RMIT since 2007 that tackle the idea of engaging the professional practice of architecture, the academic insititution and the community in a productive partnership, With the help of student participants they will reflect upon the lessons learned. RMIT Architecture Senior Lecturer Graham Crist and Brendan Jones, both Directors of the practice Antarctica, began work in the area of general practice and primary care in 2007 with the RMIT Architecture Design Studio and subsequent architectural workbook, “Rebirth of a Clinic”. This work was run in conjunction with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). This association led to a call for expressions of interest from Aboriginal Health Centres around Australia to partner with RMIT Architecture through a design studio promoting architecture for healthy Aboriginal communities. The studio’s broad ambition was to help “close the gap” in the health status of Aboriginal people, compared with other social demographics. This resulted in the commissioning of the “Home away from Home” RMIT Architecture Upperpool Design Studio partnered with the Ampilatwatja remote community in the Northern Territory. It required 10 RMIT Architecture students to work collaboratively, well beyond standard academic requirements, and produce a design for the Ampilatwatja Medical Centre located in a remote area of the Northern Territory. The group was projected into a seemingly infinite landscape and then placed in an intense and fragile community. They responded with a respectful, believable, working piece of architecture that could act as part of a scoping proposal for the community. “Seeking Asylum” is the current studio being run at RMIT Architecture in this cycle and explores the architectural issues of responding to the social, housing and health needs of people with severe mental health problems. This lecture is supported by the RMIT Design Research Institute and ArchiTeam, and is hosted by Architects for Peace as part of the Words@Bld50 Monthly Lecture Series held in RMIT Building 50, Orr St, Carlton.

Newspaper Article:

Building steps to indigenous health

Andrew Trounson

Higher Education Supplement

The Australian

November 26, 2008

CLOSING the indigenous health gap not only requires more doctors, nurses and infrastructure, but also culturally attuned architects to ensure that indigenous men in particular can brave a visit to the clinic.

Four hours’ drive northeast of Alice Springs in the 400-strong indigenous community of Ampilatwatja, one-third of the men avoid visiting the doctor because of cultural prohibitions over encountering women such as pregnant mothers or mothers-in-law.

The problem is familiar across many Aboriginal communities, and can be so bad that men have to sneak around corners and wait outside.

The law of “no room”, as the locals call it, applies equally to men and women, but at clinics where women are more accustomed to visiting the doctor it is the men who often have to make themselves scarce.

It is made worse by widespread screening for sexually transmitted diseases that has attached a stigma to visiting a doctor despite the incidence of STDs in the community being less than 2 per cent.

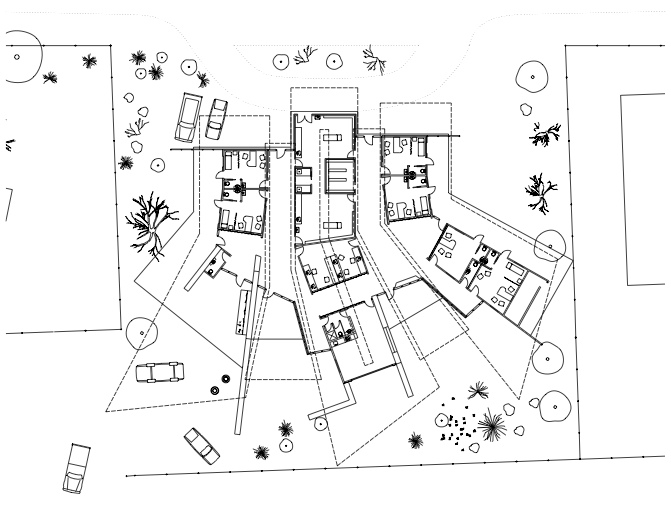

But a group of students from Melbourne’s RMIT University have designed a clinic that has distinct male and female-only sections, with no awkward corridors. There is even a car repair area that men can tinker in as a pretext for visiting the doctor.

“That’s why the men don’t come in: they are a bit frightened with the ladies always coming. But when we have this (clinic) they will be happy,” elder Eileen Bonney, 58, tells the HES.

Bonney was the community’s first Aboriginal health worker, in 1977, when the clinic was just a medicine tin and a radio under a tree.

“We think there could be a 30 per cent healthcare gain in (Ampilatwatja) men if we can get this clinic project,” says Ian Watts, the head of advocacy at the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, which sponsored the design project.

But whether the clinic, and potentially others like it, is built will depend on Canberra agreeing to fund it.

For the 10 architecture students, the experience has been more than just learning about designing for a client, but learning about a different way of life.

And they soon found that issues around fashion and aesthetics were pushed into the background by the specific needs of the community.

“Rather than starting with an aesthetic, it was the people and the need for the building that drove the aesthetic,” says Raphael Frantl, 24.

The project was no picnic, either, and involved the 10 students and lecturer Brendan Jones camping for four days while they got to know the community. By the end, almost all were sick with a stomach bug and throwing up.

“It was intense being out in the desert in the heat and the cold … but they made us very relaxed pretty quickly,” says Will Loft, 24.

The students were also careful to abide by the community’s social prohibitions. As uninitiated young men the male students particularly found it difficult to engage with the male community leaders, who preferred to talk to Jones on the clinic design.

The female students found themselves talking primarily to the women of the community.

“It was a bit scary and we were all a bit nervous, but after meeting them and seeing how friendly they were, it opened up all the positive things we can do,” says Gaudensia Olago, 23.

For Jones, himself a working architect, drawing plans in the dust with the elders was an amazing experience.

“It was about going back to basics because we had to design it around how they lived,” Jones says.